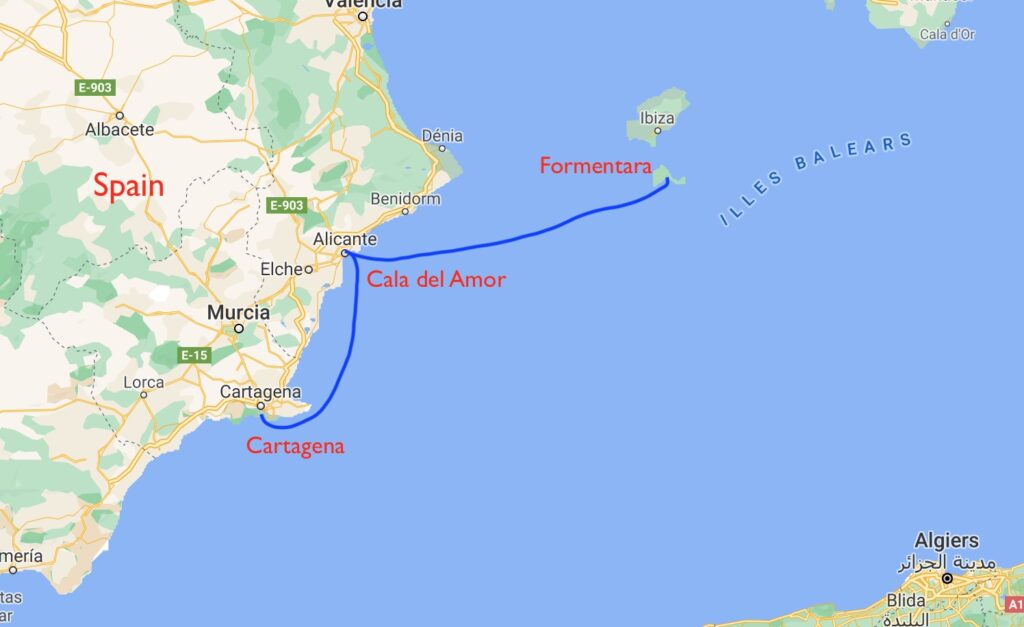

With our last overnight crossing of the summer behind us, we just had one lengthy daytime crossing in front of us. I was elated! I’m sure when we cross the Atlantic, overnights will be as natural as the Greeks making yogurt, but for now, I was placing great value on a good night’s sleep. We kissed the hedonists, the naturalists – whatever you want to call the naked men and women of Ibiza and Formentara that seemed to outnumber the clothed variety – goodbye, executing our exit as soon as there was enough light to see in the morning. We aimed to knock off the 95nm distance to the mainland of Spain in one long day, trying our best to not arrive after dark, but to pick an anchorage free of obstacles if we did need to drop the anchor after sundown.

This portion of the Spanish mainland west of the Balearics runs in a Southwest to Northeast angle. It made sense for us to point a little bit south from a direct westbound route, with a slight increase in crossing distance, to save us travel time in subsequent days down the coastline. Just east of Alicante, we found a nice protected anchorage named Cala del Amor. The reviews pointed to its practicality as a port of passage, and consequently nothing too effervescent about the scenery. This was OK. We understood this coastline of Spain was full of cities with large, tall resort hotels and apartment complexes, giving their occupants grand views of Mediterranean waters, but not a great view of those of us on the water looking the other way. It all marked a new phase in our travel, where we could expect less Ibiza-ness and more everyday urban-ness.

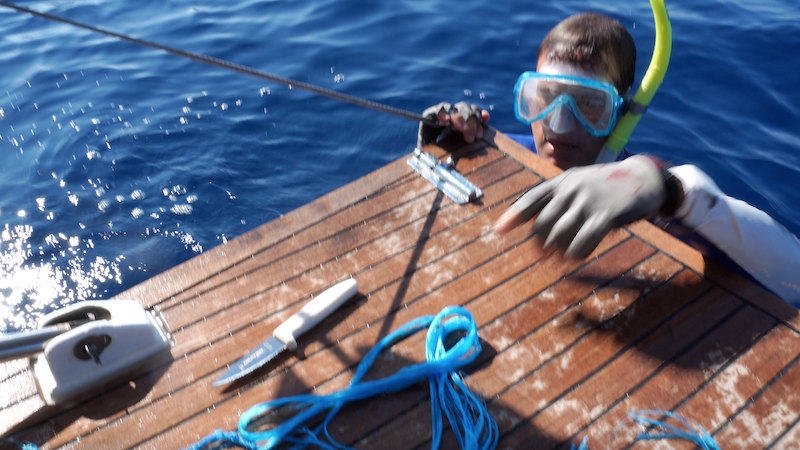

As I was admiring the mountainous interior, a stark contrast to what I had expected in my head as a flat, New Jersey-style coastline, I happened to look back in our wake and noticed a plastic bottle on a long line trailing behind us. We had had an incident earlier in the passage when suddenly the engine started to vibrate more than usual. We ended up stopping the boat and running the engine in reverse for a short period, then engaging forward again. This seemed to fix the issue. But now, again, there was a little extra shake and shimmy. After maintaining a fussy, old engine on our previous boat, we were very attuned to any unusual engine noises. Now, there was a new culprit at hand. There was absolutely no wind at this point so we stopped the boat and I grabbed my fins and mask to go overboard to inspect the situation. Normally, I don’t like to do this in open water. The boat can rock and pitch so much that you can easily hit your head on the hull when you try to resurface. But the boat was still and the water was a postcard-worthy azure blue. Diving underneath, I found the line wrapped around our starboard rudder, and from there, tangled around the propeller. It wasn’t clear if we had cut the line or if we simply had ran over the bottle and line floating on the surface during our passage. It was a special polypropylene line that floats, making it perfect for snagging once its been cut free of its fish trap. I was able to free up the line without much trouble. Oddly, I also found a plastic bag caught in the center of the propeller blades, which I removed too. I suspect this bag had been there since the earlier vibration issue and had not fully detached when we went in reverse. I had heard stories of boaters running over plastic and getting it caught in their propeller. You would think it would just get shredded to pieces. But it can also fuse together and put a boa constrictor-type hold on the whole mechanism. Thankfully, this line and bag combo came off without much of a fight, I got a refreshing swim out of the affair, and we were on our way.

As we made our final approach to Cala del Amor, we were pleased to see that we would not be alone in a bland urban expanse. In fact, there were many people out paddle boarding, fishing, kayaking, and just relaxing on their boats as if it was a holiday afternoon. The government had placed a long line of yellow caution buoys along the shore, about 300m out, which gave all of the paddleboarders and their compatriots plenty of room to practice their hobby. Surrounding us in this semi-circular cove, like a modern day amphitheater, were tall apartment buildings. But this felt surprisingly OK. It felt like we had a tiny window into the everyday summer time aquatic entertainment for the rest of the Spaniards for whom Ibiza wasn’t on the docket.

By nightfall, only a few other sailboats remained, and we passed off to sleep on a sea as gentle as a mill pond.

We were off before dawn the next day for a 65nm run down the coast to Cartagena. Just off shore of Cala de Amor, we could see the twinkly lights of Alicante ending their nightly service and the tall mountains behind the city rise up to greet the dawn’s early light. The line of buildings along the coast and deep inland shocked me. Alicante seemed as big as our larger metropolitan cities in the U.S., yet at a population of 330,000, it is only half that of Boston proper. As we moved down the coast, more cities came into view with buildings as far as you could see. Apparently we had been in the back woods of cruising waters for too long. Feeling a bit like pilgrims walking down 5th Avenue, urbanism was going to take some adjustment time.

In the late morning, as we made our way down the coast, we heard an emergency call on the radio regarding a boat ‘taking on water’. When these calls come in, rarely do they say ‘there is a boat that is sinking’. They just report that it is taking on water. Stll, everyone easily leaps without any extra assistance to a vivid picture of a boat sinking. Of course, we paid close attention to the call, trying to make out the details on a scratchy radio reception. This typically indicates that the emergency is far enough away from our antenna that our help wouldn’t be of timely benefit. Yet, we heard nothing else after the first transmission. I responded on VHF 16 with a call to the Spanish Coast Guard for a request to repeat the lat/lon of the emergency. When no response came through, I made a general call to any vessel in the area to kindly repeat the coordinates of the emergency. This is referred to as a relay, and happens quite often during an emergency. There can be a boat or land station in between you and the emergency, and they serve the critical role of being able to hear both parties and therefore able to re-transmit the details. But still it was just crickets on the radio. No response. Karen and I looked at each other, thinking without having to say it, “I sure hope we don’t have an emergency…nobody would respond!” Finally, an official sounding voice from the Valencia MRCC (Maritime Rescue Coordination Center) hailed us and after confirming our location, provided the coordinates for the emergency, whereby we both agreed that we were too far away to lend a hand. They in turn informed us that the stricken vessel was already being assisted, thankfully. In the process, as I was writing down our coordinates, I realized our longitude was 000 degrees. We were directly south of Greenwich, on the verge of crossing over from East to West longitude.

In the afternoon, the wind was toying with us, at times encouraging us to use the Code 0, then shutting down and giving us bouncy seas and light headwinds. We couldn’t twiddle our thumbs for too long lest we try entering the large port of Cartagena after dark.

As we rounded the final point and started our approach into the Cartagena’s outer harbor, we passed downwind of a large mining and refinery facility. We were to learn later that mining has been prominent in Cartagena’s history since Roman times. More recently, zinc, lead, silver and other precious metals were mined from the nearby headlands, bringing much wealth to the city. No less than twelve tankers were anchored nearby, awaiting entry to the complex, or, having done so, waiting for their next charter.

Cartagena has an ideal defensive port and was chosen by the Spanish navy as the headquarters of its maritime operations starting in the 18th century. Indeed, as we entered, fortifications and gun emplacements made it clear this port would be next to impossible to invade. Once we were in the inner harbor, a large naval shipyard and dry dock facility came into view on one side, while the other side comprised a container shipping port and commercial fishing yard. In addition two large search and rescue vessels were docked here, a particular comfort to mariners like us. In the middle of the city-front were two pleasure boat marinas, and we circled around to Yacht Port Cartagena to tie up and check in. Karen and I had decided to take in the city on a two night stay, but it only took a few minutes to witness the city’s mining history and wealth. The main historical street, Calle Major, was laid down with shiny white and pink marble slabs. The city hall was a glistening white marble structure, blessedly spared from the bombing during the Spanish Civil War in 1939. Restaurants spilled out into the walkways and alleys, tempting hungry visitors like us with an offering of cold beer and tapas.

With its large naval presence, Cartagena ended up becoming a Republican stronghold during the Spanish Civil War, as it tried to repel the fascist uprising of Nationalists, and the eventual assumption of power by Francisco Franco, a part of Spanish history we knew painfully little about. The following day, it was a quick decision to take in the Civil War Air Raid Shelter Museum, providing a tour of the network of tunnels under the city sufficient to hold 3300 civilians, one of many shelters built during the later half of the war.

An equally quick decision was the National Museum of Underwater Archaeology. I’m a sucker for any type of maritime museum, and we’ve been to plenty of them over the years, so a museum on underwater archaeology was like a wet dream. The piece de resistance was the story and artifacts from the Nuestra Señora de la Mercedes, a Spanish frigate controversially sunk by the British off the coast of Portugal in 1804 despite the fact both countries were at peace with each other. Onboard were gold, silver and other valuables destined for Cadiz from South America. Fast forward to 2007, an American salvage company name Odyssey Marine Exploration discovered a wreck with some 500,000 silver and gold coins. This triggered a Spanish government lawsuit for recovery of the valuable historical items, dubbing the American company as a looting operation. Eventually Spain won and an estimated 14.5 tons of silver and gold coins were delivered to this incredibly fortunate museum in Cartagena for jaws-dropped visitors like Karen and I to enjoy.

It was undeniably clear this wreck was a flashpoint for Spain, with anger equally conveyed upon the British for sinking their vessel during peacetime, and Americans for salvaging cargo that did not belong to them. Like a fight over neighborhood property rights, I’m glad that time had appeared to heel these wounds, while enriching the cultural heritage of Spain.