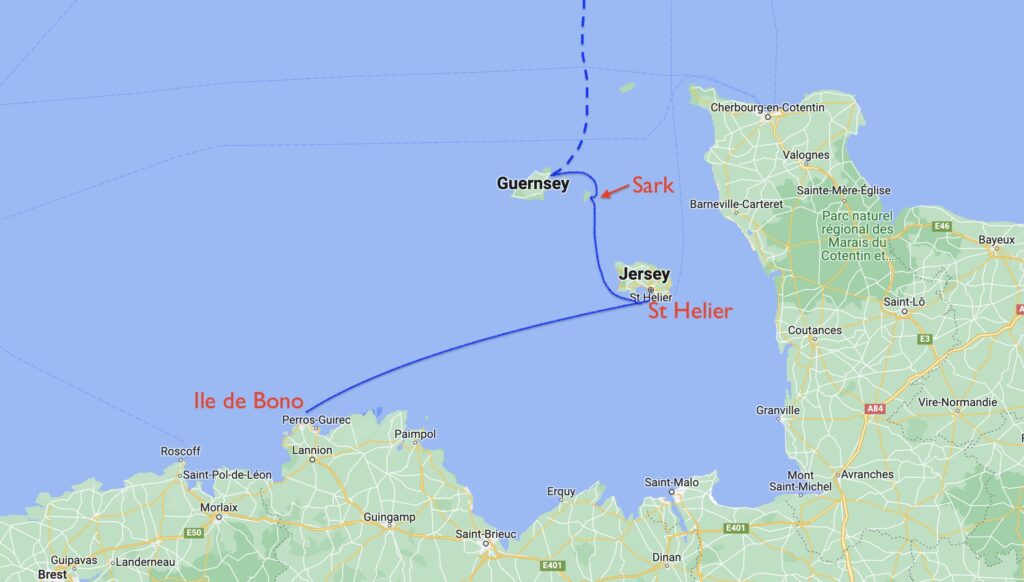

We raised our anchor at first light from the bird sanctuary at Ile de Bono and headed northeast to the Channel Islands. Au revoir, France! We hope our paths cross again some day! Before this summer, I had only a vague understanding of the Channel Islands – their geography and their history. I knew they were somehow connected to the UK, and that their residents endured much hardship during WWII, but only because I had seen the now famous movie “The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society”. Sure, you can learn little tidbits of history from Hollywood, but we were very excited to see the Channel Islands with our own eyes and learn firsthand about their people and their culture.

Winds were forecasted to come out of the northwest for our 60 mile run, a distance that would make for a full day, but even more so, we were especially eager to get going at first light to time our arrival in Jersey before the marina at St Helier closed. The marina was the type that had a sill that held water inside the marina, but required you to arrive at high enough tide to cross over the sill with sufficient depth for your keel. St Helier has about an 8 meter tide range, which allowed the marina to keep the sill open from about 2 hours either side of high tide. If we missed our window, we might have to wait for up to 8 hours before we could try again, putting our entry in the middle of the night, an unpleasant prospect any way you look at it.

As forecasted, the wind filled in nicely at 15-16 knots, giving us a perfect beam reach using our Code 0 sail. With water currents favorable in our direction as well, it seemed like we had our arrival timing in the bag. Karen and I moved right into a 2 hour watch schedule. I am normally ready to hand over the wheel at the end of my watch and go down below to read, or fix something, or make a meal, but conditions were so ideal, it was hard to give up the helm. Every once in a while, the wind would soften and we would motor sail for a few minutes to keep our ETA in check, but then the wind would return, as if it was also going through a momentary watch change. In the afternoon, the wind built to 18-19 knots and when I rechecked the forecast for the day, it was remarkable how precisely the reality, both in wind direction and strength, matched to the forecast. We had been noticing this throughout France. It was almost like the French, in their mastery of sailing, had also mastered the wind predictions for their favorite sport. We had grown accustomed to forecasts in the Med, particularly around Greece, to be wildly off in strength. A forecast for 10 knots could easily turn into 25 knots. Here along the north Brittany coast, we began to trust the forecast like a passenger trusts the Swiss railway service.

Soon a faint outline of Jersey came up over the horizon, and we pushed forward with the autopilot in control as we approached the entrance channel. Jersey is not an anchorage hopping paradise. The main city and harbor of St Helier runs a sort of one act play. If you want to land by boat and see the island, you have only one main choice. This means that one is also competing for navigable water with all the cargo freighters necessary to supply an island economy. This was our first introduction to a busy Northern Europe commercial harbor entrance. Traffic is typically controlled by a radio service named VTS, or Vessel Traffic Services. They act like air traffic controllers, making sure that large freighters and ferries are spaced out enough to avoid collisions, and that private boats like ours keep out of their way. Each port’s VTS operates on a specific VHF radio channel and sometimes you are simply required to monitor the channel. At other ports you are required to radio in to receive approval before entering (and exiting) the port. It wasn’t clear what St Helier’s VTS wanted, so I called in anyways and they confirmed it was safe for us to proceed to the marina. A series of vertical lights on the tall breakwater, showing green, white, green, also confirmed that two-way traffic could be expected. As we doglegged through the outer breakwater and passed ships at berth, long shadows cast over Sea Rose as if we were David confronting Goliath. The entrance to the marina came into view and I struggled to identify its vertical light signal. It looked like there where three vertical red lights, the signal that the entrance was closed. As we got a better view, the digital depth gauge, showing how much water was over the sill, read a disturbing 0.0. How could that be, we wondered. A placard made it all clear, stating that the marina was under renovation. Sure enough, only a few boats were nearby, and they were all rafted up to a single pontoon outside the entrance, a makeshift overflow area in the deeper water of the commercial shipping berths. An immaculate Oyster 65 sailboat was our only option for rafting, as the other rafts were four boats thick and comprised of smaller boats. It’s a dicey endeavor to tie to the outside of a raft up when the boats inside of you are all smaller and more vulnerable than you. It took a bit of convincing to get the captain of the Oyster, a multi-million dollar boat at any age, to put out fenders to complement the ones we had, an odd response, but we soon were swapping stories and advice as we learned they were from Denmark and heading south to the Med.

It’s always a special moment when you step off your boat in a new country. The kinship of landing in an English speaking country held additional excitement for us. We paid for a two night stay, found an ATM to fill our wallets with British Pounds instead of Euros, and we hoofed it into town to find a place for dinner to celebrate. Being in the UK, I wasn’t expecting gourmet dining. All I needed was a cold beer and something warm to eat. To our surprise, my hamburger and Karen’s salad were fresh and lip-smacking tasty. Something had changed since we were last in the land of the Brits.

I should clarify some political terminology here before we proceed. I have been loosely using the words UK, Britain, and England interchangeably, but there is a distinction when it comes to understanding the role of the Channel Islands. Jersey, technically the Bailiwick of Jersey, along with the Bailiwick of Guernsey depend on the UK for defense and international representation, but they are curiously not part of the UK, nor do they receive any financial help from their larger neighbor. Both balliwicks have their own laws, elections and representative governments. The UK is strictly made up of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Make sense so far?! Now, if you were thinking the Channel Islands were part of Great Britain, you would be incorrect. Great Britain is just England, Wales, and Scotland. However, perhaps you were thinking of the term ‘British Isles’? If so, you are on to something! The British Isles comprise Great Britain (England, Wales, Scotland) plus Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and finally our special friends, the Channel Islands. There will be no quiz as, like any teacher, grading homework comes out of our precious evening time!

Standing out off the city of St Helier, surrounded by water at high tide, is the Elizabeth Castle, built in the 16th century and so named by Sir Walter Raleigh, the governor of Jersey at the time. Avid readers of our blog from years back, or knowledgable historians of the U.S. mid-Atlantic will recognize his name as the man behind the ‘Lost Colony’ expedition that landed on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, but due to a three year re-supply delay, the settlers disappeared without a trace. You’ll find out more about it in our blog post here.

Elizabeth Castle can be visited by a duck boat style craft when the tide is in, but when we visited it in the early morning, the tide was so far out, you could walk along a moist concrete path, past mooring buoys dried up on the sand. The city tightly controls when you can walk out to the castle and when you need to wait for the boat. To make the point clear, we had until precisely 10:32am to get back to the mainland.

Jersey today is a busy financial center, with banks on nearly every corner, a result of generous laws on taxation. Business taxes range from 0-10% and the maximum personal tax rate is 20%. Not surprising, with corporate interests so strong in St Helier, tourism was a lesser commodity. But as soon as we hopped on a public bus away from the city, the island started to take on more character. To understand the impact of WWII, we set our sights on the Jersey War Tunnels, an underground complex built by the Germans as a hospital and control center. At the entrance, we were each given a replica of the identity papers for one particular island inhabitant during the war, seeing life through their eyes and learning at the end of the museum what their fate was. The German occupation lasted five years, with the first few months reported to be somewhat tolerable for those who had not chosen to evacuate, leaving behind their household possessions and abandoning their cars at the waterfront. But freedoms were gradually removed, life became more oppressive, and food became scarce. Neighbors ratted out fellow neighbors, if only to gain favor with the Germans and slightly better rations for their newborn children. One section of the exhibit aptly called it the ‘rot of war’. When D Day came, their food became even more scarce, as deliveries from German-occupied France were cut off. Finally, on May 9th, 1945, nearly a year after D Day, the island was liberated. It was a chilling reminder how no corner of the German occupied territories were spared extreme suffering.

Back at the boat, we were part of a four boat raft up and had to ask the two outer boats to leave at 7am the next morning when we planned to get underway, a regretful action, but one that everyone that decides to raft has to deal with. It is an unspoken rule that if an inner boat needs to leave early, you need to break up the raft at that time, circling around to retie to the raft if that is your desire.

With clearance from VTS to exit the harbor quickly, we stowed fenders and lines without delay. The reason for the hustle was soon clear. A large passenger ferry, the length of a medium-sized cruise ship, had just left its berth. The narrow harbor channel left little room to get out of the way on an account of the girth of the ship. Sure enough, the captain reached for the horn immediately, letting out the five blast ‘Danger/Doubt’ signal. We moved as far over as we could, but a sailboat from our raft up ahead of us was not as quick to clear the channel center. I was hoping the five blasts were meant for them, not us!

There are multiple ways to leave St Helier by water, and the main channel we had intended to use was a longer route than the path the ferry was taking. We figured if the ferry can do it, so can we, as we followed in their wake. Up ahead, another route close to the shore became obvious and attractive, deep enough for us but not enough for the ferry, and we diverted into it, as big head winds started kicking up large seas and slowed down our speed considerably as we motored straight into. It felt like we were covering as much distance going up and down the waves as we were going horizontally over the ground. Sea Rose, with its flat hull bottom, doesn’t do well in these conditions, slamming down the backside of waves with a shuttering crash shooting white water flying out to our sides. We were now in the dreaded scenario where big headwinds were being counteracted by strong tidal current in the opposite direction, making the waves even steeper. We rose up one particularly steep wave and the bow of Sea Rose descended down the backside with such force that it dipped into the sea, causing a wall of water to break over the foredeck, strike our dodger, and fly over the bimini. Leftover seawater on the deck came rushing back to the cockpit and took painfully long to drain through the scuppers. Our raft up neighbor was making better progress under sail further off the coastline. The solution was clear, and we took our first opportunity to cut through a deeper section of the shallows around us to get further off the Jersey coast, where we too set reefed sails for a course north towards Guernsey. Dark gray clouds raced across an unfriendly sky above white-capped seas but at least we were sailing, doing what the hull shape and rigging of a sailboat were designed to do.

Once we cleared the northern point of St Helier, our favorable current eased considerably and to our amazement we were immediately in flatter seas. We didn’t have the added boost of the current, but this was a small price to pay for a more manageable sea state. But no sooner had we adjusted our mindsets than we were back in a section of strong current – we must have passed through a brief current eddy before – and the steep short-period waves were back. There was no sense trying to sail close-hauled in these kinds of conditions, so we eased the sails to a beam reach and set a course for one of Guernsey’s smaller offspring, the island of Sark. With the wind and waves perpendicular to our course, steering was very difficult. A breaking wave would appear just to our windward side and we would both take cover, only to find that the wave slid under our hull without incident, like we had some invisible force field around us. Then, another wave rose up next to us, but this time its position was such that when it broke, it struck the windward side of our hull with all of its energy, producing a deafening thud, and sending white water high up and back into our cockpit, somehow missing me at the windward helm station but finding Karen at the leeward helm, completely drenching her and the complete aft section of the cockpit. Thankfully, she was wearing her full foul weather gear and boots, which minimized the water intrusion but not the shock value.

We pushed on towards Sark and wasted no time to find the first reasonably workable anchorage, inside of a few rocky outcroppings but still exposed to the wind as it raced down the side of this strangely tall but flat topped island. Foul weather gear was whipped off quickly as we freed ourselves to get some rest down in the cabin while Sea Rose whipsawed her way back and forth on a tight anchor line in the 20-25 knot winds. But as the saying goes, you can put lipstick on a pig, but it is still a pig. This anchorage was not going to work for an overnight if we hoped to get any rest. We found the antithesis just a short distance around to the eastern side of the island, far better protected from the strong winds and with the comfort of a few other cruising sailboats. I couldn’t believe this small cove could be so flat calm. High square cliffs on the shore were doing their job admirably well.

Sark has the distinction of being a car-less island, with tractors being the only mechanized equipment to manage the various working farms. Transport is by horse drawn carriage, bicycle or your own two feet. An island can make these kinds of lofty idealistic rules when it has the freedom and independence to do so. Sark is a royal fief, a form of feudalism, and while it is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, it sets its own laws and has its own parliament. Does it sound like a pattern is emerging on the Channel Islands?!

It felt fantastic to get off the angry seas and walk through the island’s little villages, past simple homes with homemade jam set out for sale to the few visiting tourists like us, and a few shops selling necessities. When I gave one of the shop keepers one of my fresh new British Pound notes for a couple of cold drinks, she replied, “Oh, you probably want British Pound change back, right?” I gave her a look like I had started to perfect back in Jersey – we are both speaking English, but I surely don’t understand what you are saying!

On the western end of Sark, a very narrow and tall stone bridge had been constructed by German prisoners of war in 1945 to allow for passage across the isthmus to Little Sark. Winds buffeted us as we took careful steps across the one lane bridge. Photo taking had to be sprightly lest the gusts rip the camera out of your hand and send it tumbling down the cliffs to the sea below. Looking over the edge, I noticed where we had briefly anchored earlier today.

Back in town and finding ourselves at the only watering hole in town, the Mermaid Tavern, we felt the need to quench our thirst from all of the walking. Here, a dozen locals were nursing beers while a few of their offspring waited patiently by their side, or like one hound dog, at their feet. It took no effort on our part to stand out from the crowd; quick glances in our direction and then away served to confirm our outsider status more than any words could. After one round, it felt appropriate to move along.

We had been trying diligently to get up north to Guernsey, and the next morning’s weather gave us the opportunity to do just that albeit with the help of the engine against a strong headwind. Like Jersey, the anchoring options are quite limited around Guernsey and most sailors opt for the main harbor of St Peter Port, but the similarities stop there. Instead of big noisy freighters next to you, and banks on every street corner, we were enchanted by the echoes of laughter across the pontoons as boat crews exchanged high tales. Multiple boats flew the same rally flags celebrating their mutual accomplishments of reaching the Channel Islands from the UK. The staff of the well-run Victoria Marina came out to greet us and show the path to an open dock space, always a welcome gesture to first-time visitors like us. Other boaters happily chugged past us and over the sill into the inner Victoria Marina docks, as the digital gauge could be seen slowly dropping, an experience I would be very happy not to have to encounter this summer.

My struggles to recognize scenes ashore from the movie led me to learn that it was actually filmed in Devon and Cornwall, across the channel in southwestern England. But this unfortunate fact did not dissuade us from enjoying this charming seaside town. Victor Hugo lived out his later years here while writing, among other works, his classic Les Miserables. Bookings to tour his home’s majestic interior had already quickly filled up for the day. We opted, instead, to hike up to the top of the Victoria Tower where we used a huge old skeleton key to open the main door. The key was leant to us by an even-keeled librarian down the street who appeared non-plussed to see us giggling with amusement that we were trusted with both this rusty artifact and the responsibility to turn off the lights and lock the door upon our exit.

There is a certain kinship between Brits and Americans. We have a few touchy subjects in our past – religious persecution, the Tea Party, the War of 1812, like the quarrels of young siblings – but now I feel like we are closer to aging college fraternity brothers, marveling that we’ve made it past the awkward years while throwing back a celebratory beer or two. With kinship comes curiosity, and complimenting Brits infatuation with beer is their more sophisticated relationship with tea. As Karen and I walked past the stately-named Old Government House Hotel, signs for Afternoon Tea gave us an excuse to both rest our weary legs and to fill in that hunger gap between a lunch that never materialized and a dinner absent a plan. You might recall that Anna, the seventh Duchess of Bedford, was similarly stricken with hunger pains back in 1840 while waiting impatiently for the 8 o’clock dinner hour to arrive. What a Duchess wants, a Duchess receiveth, and she soon began the indulgent trend of tea, bread and butter late in the day. Indulgent didn’t begin to describe our Afternoon Tea, as a three layer serving tray arrived at our table overflowing with scones, muffins, sandwiches and a variety of desserts that had been prepared by steady hands. This was all washed down with our own tea selection – I had chosen Chamomile, Karen a lemon/ginger concoction – brewing in separate football-sized tea kettles. The whole affair was so brilliantly overabundant we could swiftly pare down the day’s todo list by checking off lunch, dinner and a glimpse into British high society.

Our introduction to the nuances of the Great British Isles was well underway. We would be sailing away from these delightful islands at 5am the next morning to strike out across the infamous English Channel, full of big currents and heavy shipping, hoping for another peek into the lives of our British brethren.

Be sure to also checkout the video content on our LifeFourPointZero YouTube channel. We regularly post updates on our sailing adventures, as well as how to videos on boat repair, sailing techniques, and more!

Loved this installment of your adventures.

Thanks Ken, appreciate it!

Sometimes I feel a little sea sick just reading your posts! What great adventures. We’ll definitely wait until you guys are sailing in less challenging waters before joining you on-board!

Hi Tony! Let’s keep in touch on that!

You’re such a good writer Tom that I can feel the spray from the gunn’l in my face. Thanks for sharing your adventures with us landlubbers.

Thank you very much Jeff, really appreciate it! Glad you enjoyed it! Take care.