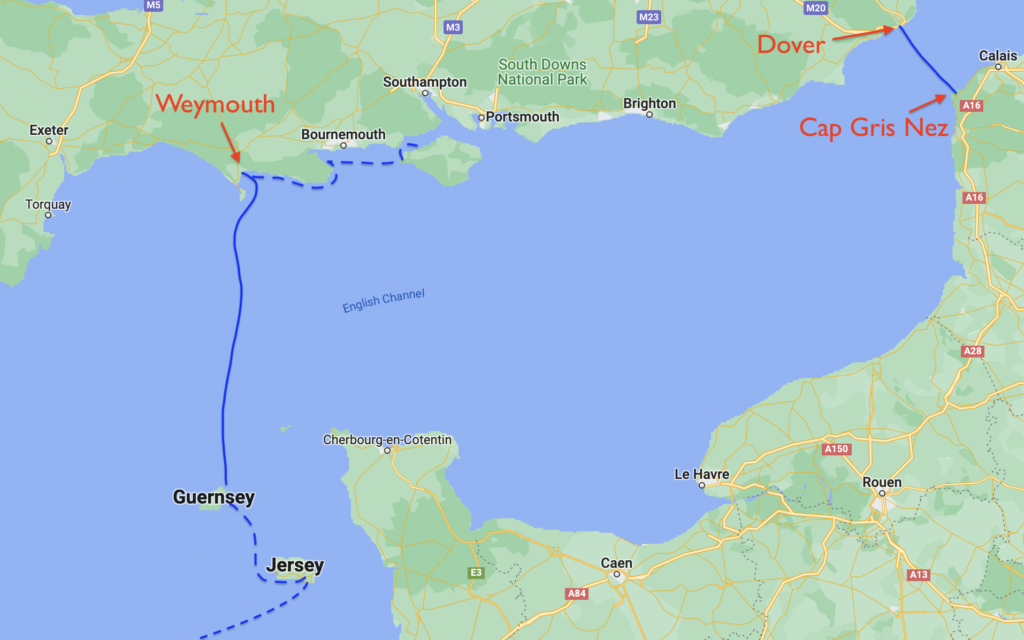

When I think of the English Channel, my mind goes immediately to the amazing athletes that have swum across this iconic waterway. It is a 21 mile endeavor at its the narrowest point from Dover. I remember as a kid seeing live TV broadcasts of these swimmers, out in the turbulent waters swimming all through the night. Enduring for so long was impressive given that I get winded swimming from one end of the pool to the other. For our crossing of the Channel on Sea Rose, we would be in the safety of our cockpit and exerting ourselves far less, but yet some of the same challenges were present. The English Channel is considered the most heavily traveled shipping route in the world, with so many containerized goods heading to Northern European seaports, as well as supertankers coming out of North Sea oil fields, and busy passenger ferries zipping around in between them all. There are designated shipping lanes – called Traffic Separation Schemes on the nautical charts – where the majority of the ships transit in and out of the Channel, but at times it can seem like bumper-to-bumper traffic on an expressway.

The other main challenge is the tidal currents. I have written in previous blogs about the extreme tides in this area of the world, with some ports reporting tide ranges equivalent to the height of a three story building. That’s a huge amount of water that has to flow in and out every 12 hours. We would be crossing the Channel at a much wider point than where the endurance swimmers cross – some 70 miles from Guernsey to Weymouth – but still the currents run between 2 and 3 knots . If you don’t pay attention to your course, you could be easily set far down stream from your destination.

The final challenge was one we encountered right away upon leaving Victoria Marina in Guernsey, at the ripe hour of 5AM – fog! We are no strangers to fog, having sailed throughout the coast of Maine, and Sea Rose is equipped to handle it with a good radar and a new foghorn, but we cautiously motored out the channel watching the radar screen and AIS very carefully. There are a large number of rocky islets, and buoys marking these hazards, off the island, which can show up on the radar just like a boat to our eyes unfamiliar with this area. Once we were a few miles off the coast of Guernsey, the fog layer lifted and we were suddenly and happily in clear blue skies. Fog is a persnickety phenomenon. At its worst, you can’t see the bow of your own boat. But it can clear as suddenly as opening a window shade.

Our fun wasn’t over yet though. We had been motoring out in a strong favorable current, making for a very attractive ETA into Weymouth, but all of this volume of water collided in front of us with a counter current flowing out of the Channel, causing overfalls. We had encounter this type of agitated water along the Portuguese and Spanish coasts, where water ebbing out of a river hits the tidal inflow from the sea. It can look like a benign white line from a distance, but as you get closer, the three dimensional size becomes clear, and once you are in it, large swirls of ocean water the diameter of a large city bus shove you off course quicker than can be corrected by your own rudder. The water from these overfalls literally went over our foredeck, and came racing down the side deck to find Karen sitting at the helm, dousing her with cold English water. Once on the way to Sark, and now just a few days later leaving Guernsey, she wasn’t having much luck with Poseidon!

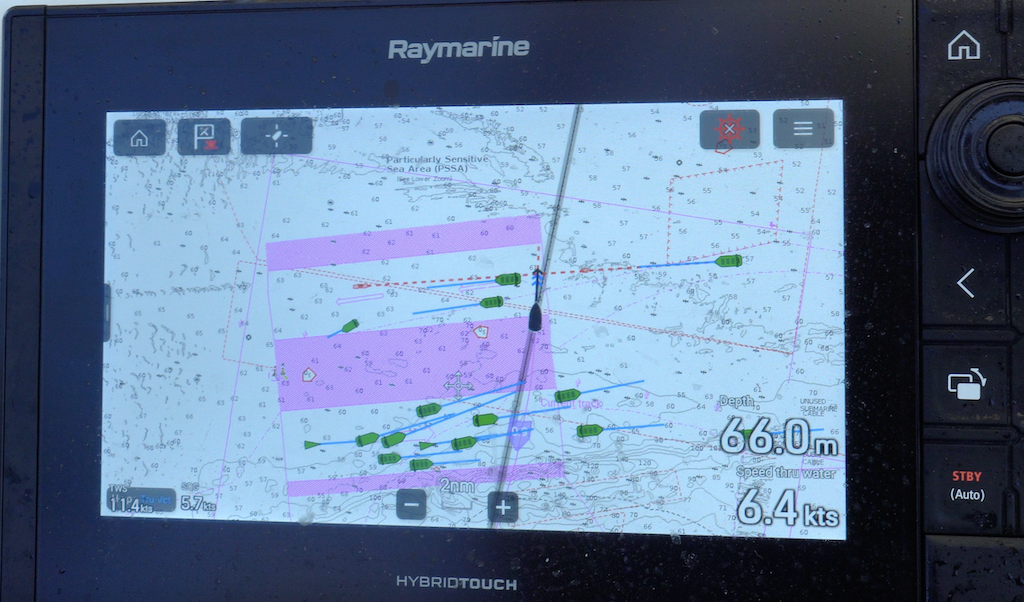

Clear of the overfalls, we unfurled sails and set a close-hauled course for Weymouth with a building breeze. Soon we were seeing winds upwards of 18 knots, pushing us to put a reef in the mainsail. We were nearing the inbound lane of the TSS, and I could see on the AIS a line of ships ahead of us, with a rare and fortuitous gap that looked like it would line up with our timing of crossing their lane. We slid through the gauntlet, perfectly spaced like pieces of airport luggage on an automated conveyor belt. The TSS had an equally wide space in the middle, a boulevard median if you will, to ensure no ships collide with oncoming traffic. This gave us time to look at the outbound traffic on AIS, and note with ease that a large gap appeared behind the ships directly ahead of us. But one of the fallacies of AIS is the line-of-sight broadcast range, meaning that as more ships appear above the horizon, they would backfill the empty outbound lane on our chart plotter with a continuous emergence of new vessels. We slowed down slightly to take the stern of one ship, and scooched quickly across in time to be free of the next ship’s bow.

As we closed the coast of England, our next challenge was how to negotiate Portland Bill, a large peninsula jutted out from the coast and around which the tidal current can accelerate to speeds that can not be overcome by a sailboat’s modest engine. In addition, the current in the main part of the Channel was now shifting to push us west of Portland Bill, when we needed to pass on the east side in order to make the harbor at Weymouth. In my mind, I was seeing the hungry Kraken, sitting at Portland Bill, enjoying the prospects for dining tonight on unsuspecting small boaters. Worse, if we went too far east, we would cross a string of shallows labeled on the chart as the ‘Shambles’, comprised of long angular streaks in the sea floor resembling the swipe of a grizzly bear’s claw. What kind of welcome was this? Had the British lost their air of congeniality?!

We eventually threaded the needle past Portland Bill and found ourselves at the delightful seaside community of Weymouth. As we walked around the waterfront, it occurred to me that despite so many towns on the U.S. east coast that try to copy the look (and sometimes the exact same name), classic English towns like these are so steeped in maritime history and built with old hand-crafted stone and wooden beam materials that any attempt to emulate them is futile. When you’ve got many centuries of history on your side, it is hard for others to play catch up.

We caught up with a few beers and a couple plates of when-in-rome-do-as-the-romans-do inspired fish and chips. We had arrived on a Friday yet it seemed like every resident and tourist alike were ensconced in one of the many outdoor bars and cafes soaking up the late afternoon sun like they had just been teleported to a Caribbean island with swaying palm trees. After questioning a nice young couple next to us, we found out they hadn’t had sunshine in a very long time. And with that, it became clear. Our pilgrims left under the guise of seeking religious freedom, but really it was all about a sunnier climate!

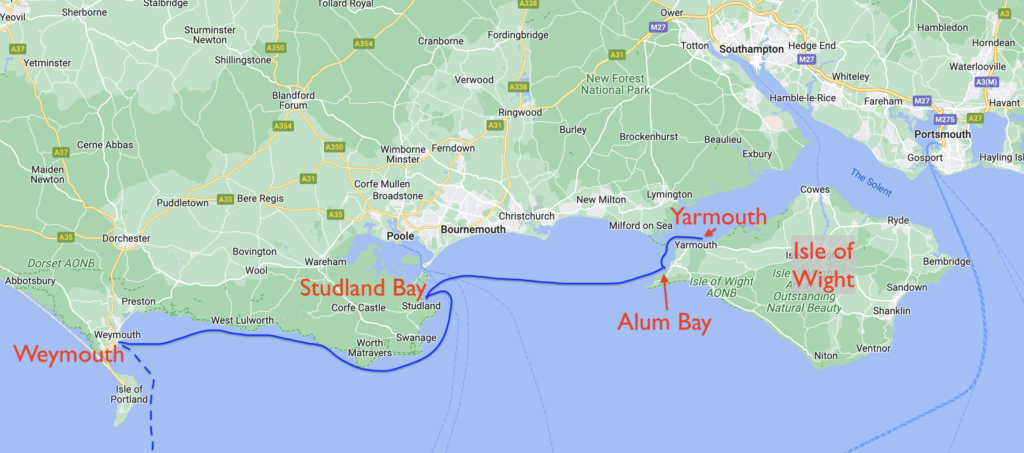

We had arrived in Weymouth several days before our friends Steve and Julie would arrive, and you can only absorb so much charm in one sitting, so we headed east along the coast for a quick overnight. The shoreline here rises quickly into dramatically tall white chalky cliffs, the kind that drop vertically to a sand beach below, looking as if they would continue straight down to the earth’s core if you were to dig away the sand. I was very excited to see the white cliffs of Dover in a few weeks, but I couldn’t imagine them being more beautiful than this gem of a coastline. Surely there had been a mistake and the team of judges on such matters hadn’t made it out of Dover yet.

Just beyond, we nosed Sea Rose into what has to be the most perfectly round harbor in existence – Lulworth Cove – its only competition the Voidokoilia Lagoon in Greece that we had visited two years ago. With the summer season starting to come into full swing, we didn’t expect to have much room to anchor. One sailboat had just raised their anchor and motored past us on their way out, giving us a chance to quickly drop our anchor in their spot before someone else grabbed it. With Karen behind the wheel, born and bred in the New York way of living (“love you, honey!”), we have perfected this lean-in technique to anchoring in busy harbors.

As special as this cove can be, you need to get off your boat and walk the cliff paths to really take it all in. I was beginning to wonder if I’d soon max out my phone’s storage with all the pictures of cliffs falling to the sea and white puffy clouds lazily drifting across the big blue sky.

Most of the boats had left by the time we settled back onboard for a quick dinner and an early bed time, with the only issue being a neighboring powerboater running their generator into the wee hours forcing me to envision myself as a highly trained seal team six member, slithering my way over to pour saltwater (or a banana) down the offensive machine’s intake. Eventually I did fall asleep. However, Karen, in addition to her marksman-like anchoring instinct has the unfortunate burden of being a light sleeper, and proceeded to wake me at 1am, thinking that she heard a sound like us tapping another boat. How she got paired with me, who sleeps like a log and can’t muster any brain activity when suddenly woken, I will never know. Regardless, we both climbed up into the cockpit and looked around. Nothing was amiss, so we headed back down, each making a late night people-of-a-certain-age visit to the head. But then the proverbial shit hit the fan. Suddenly, a huge bang and crunch reverberated through the hull of the boat, like a giant had taken a huge sledgehammer and slung it against the keel. It hit with such force, it knocked Karen off the seat of the head. We scrambled back up to the cockpit, yelling alternatively, “Holy shit!” and “What the hell was that?”. With the instruments on, we could see the depth pop on and reveal a value of 0.1m. We had hit bottom, and the bottom specifically was a rocky ledge coming out perpendicularly from the shore. We should have known. We had paddle boarded over this ledge before nightfall, wondering if our little paddle board skegs would bottom out. Our 2.2m keel didn’t stand a chance. We had skipped a critical step earlier in the day, in our haste to grab an open anchor spot, to circle with the boat to check the swing radius and depths. So here we were, in the pitch black of night, when everything wrong happens, and our adrenaline-induced racing hearts trying to kick our brains into gear. We knew we had to move quickly. Another sharp strike on the rock ledge could severely damage the keel, or worse, the rudders, leaving us with no way to steer to safety. And, without a reference point, where was safety – forward, back, right or left? I raced to the bow to start raising the anchor – it would have to come up either way – while Karen kicked over the diesel and began inching us slowly forward. Gradually, the depth gauge read slightly higher numbers. We were trending in the right direction. Once the anchor was all the way up, we used a spotlight to find the other boats anchored around us, and ever so carefully followed our track line on the chart plotter out of the cove, making the assumption that if we arrived on this line, it was deep enough for us to leave on too. A light chop was breaking at the mouth of the cove, as Karen steered us out exactly through the center between the rock cliffs.

We were relieved beyond belief to be out of the cove and in deep water, but our elation quickly faded as we contemplated where to go next. We purposely make a habit of minimizing any night time navigation, with the exception of multi-day ocean or open-water passages, because of the unnecessarily high risk. The light chop we had exited through was the result of a light onshore breeze, and we quickly determined that sailing back to Weymouth would be the safest option. In coastal waters, you have the risk on a dark night of running over fish buoys and other detritus. When you are motoring, this can quickly disable your propellor. When sailing, it might snag on your keel or rudder, but most of the time you will still be able to sail.

We soon had both sails unfurled and were sailing along at 7 knots on a perfectly amiable beam reach. If it wasn’t 1:30am in the morning, we might have been inclined to put the autopilot on, make sandwiches and debate the news of the day. Entering the town docks at Weymouth in the dark was out of the question, but we did find plenty of room to anchor off the town’s broad sand beach. By 2:30am we had the anchor set, sails furled, foul weather gear stowed, and heads on pillows. Re-running the events of the night in our brains, though, prevented sleep to come when it needed to.

Back on the dock at Weymouth, our early arrival allowed us to pick our own spot to side-tie to the floating pontoon. But the marina, in order to accommodate as many boaters as possible in this full swing of summer, allows other boats to raft up to you until the whole shebang sticks out so far that other boats can’t enter the harbor. While you get the advantage on the inside of one step to get off to the dock, other boaters rafted up to you are constantly walking back and forth across your boat to get to theirs, all day and into the night until the pubs close, then early in the morning to the showers or to take a dog for a walk. In our case, with four boats rafted up by nightfall, that put all of the pressure of those boats on our cleats and dock lines whenever the wind would surge or there was wave action. And meanwhile, while we were being trampled on and lines and fenders were being tweaked, the marina made four times the income for each dock space!

We channeled our stress in the manner suitable to any proper Englishman, by ordering a tall beer at the closest pub. Although this time we skipped the lifespan-reducing fish and chips and opted for a surprisingly tasty Caribbean jerk chicken. When the young waiter finally brought our bill – it can take a lot of pleading in these parts to get closure on your meal – I gave him some of our crisp new 20 pound British notes that I had ATMed back in Jersey. He looked at the money and paused, remarking “Wow, I haven’t seen one of these before!” Confused, we let him walk away while we tried to understand why a waiter hadn’t seen such a common currency denomination. He arrived back shortly after, reporting the news that his boss can’t accept our money. Astonished, Karen asked why not, and we quickly learned that the pounds we had were Jersey British Pounds, not the standard Great British Pounds or Sterling! They had the picture of the Queen on them, so we thought if she blessed them, they would be good to go. I rushed down the street to another ATM to fetch some proper GBP notes to pay our waiter. Concerned that we had 300 pounds of possibly useless Jersey currency, I entered a bank the next morning to sheepishly inquire about exchanging this money for GBP. The polite young banker, in starch white shirt and navy blue tie, took all of the Jersey money from this hair-tossed, faded shorts wearing, sandal clad drifter. When I explained my predicament that we weren’t headed back to Jersey, he chuckled but continued to dole out GBP notes one-for-one, while showing me in his bank drawer that he had other Queen-emblazoned pounds from Guernsey, Scotland, Northern Ireland and even Gibraltar… who knew! My confused reaction to the merchant in Sark that offered to give change in British pounds was now becoming clear.

After reprovisioning the boat at a close-by supermarket, whose variety of inventory both in groceries and housewares would put to shame most stores back home, we welcomed our friends Steve and Julie onboard for a few days of sailing the southern coast of England. Timing your departure is important here unless you fancy sailing along in a counter current and making no progress by land, so it was no surprise that our departure from Weymouth coincided with many other boats headed east. Karen and I were eager to show our guests the beautiful white chalky cliffs, while putting Lulworth Cove quickly in the rear view mirror. We pushed on down the coast to find an entirely new stretch of white chalky cliffs, as if we were following a geological fault line of rock. As we rounded up and furled our sails, thin pinnacles of white rocky needle-shaped rocks stretched into deeper water. Searching the chart, we found the outermost pinnacle was named ‘Old Harry’s Wife’, with I’m sure a good story to back it up. We had entered the broad Studland Bay with ample opportunities for anchoring, a welcome relief from what looked like many weeks ahead of single-option marinas.

Ashore, we followed a coastal walking path out to the point, a trail that at times followed the cliff edge with only a tuff here and there of grass to disguise where the dirt ended and a quick fall to your death awaited. It was not a trail amenable to small children, pets or Instagramming adults trying to snap the perfect selfie!

This area of southern England is dominated by, some might even say part of a gravitational force field around, the sailing mecca that is the Isle of Wight. As we inched closer to this prominent island off of Southhampton and Portsmouth, images ran through my mind of close-hauled boats racing around the island, images that regularly adorn British and international sailing magazines, books and movies. 5000 boaters race each year during Cowes Week, and many more can be found sailing around these waters called The Solent. The race wasn’t starting for another month, but the concentration of sailboats was increasing rapidly as we approached the Isle of Wight. Our destination was a small nook in the western end called Alum Bay. The anchorage is just outside of the main stream of rapidly flowing current and is very exposed to any wind from the west, so conditions have to be just right in order to stay overnight, conditions we fortunately were experiencing for the next few days. If there is one classic image of the Isle of Wight, and British sailing in general, it has to be ‘The Needles’, a set of very tall white pinnacles lined up in such a way with those across the water in Studland Bay to be clearly part of the same geological origin.

We dropped the hook in ultra clear water in the shadow of cliffs close to two hundred feet tall composed of mineral rich dark brown, light brown, pink and white rocky layers. We were all left to wonder whether any other place on earth could rival this spot for its beauty.

That is, until we turned to look behind us and found a clunky old chair lift scaling the cliffs to shuttle visitors down to the beach from a honky-tonk amusement park up above. We landed the dinghy and joined the throngs of humanity queued up to ride the chairs back up, before heading out on a cliff-defying hiking trail out to The Needles. Whatever forces of nature created these incredible pinnacles and cliffs also produced a high flat plateau, and as we followed the marked trail, it led us past old wooden gates into pasture land still clutching springtime with thick green grass and young flowers. I could have walked all afternoon, absorbed in one’s thoughts and reflections that can only come at the hands of such raw unfettered beauty. The trail ended at a prominent knoll, marked by a tall monument in a fitting memorial to poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

In the morning, we set sail to tack around the corner to Yarmouth, a popular harbor on the north side of the Isle of Wight. They didn’t take reservations, following a strict first come, first served policy, so if you are arriving in June and hope to stay overnight, you need to get there early. They also manage the boat traffic very closely, with several marina skiffs circling the entrance to instruct you on where to dock. With the immense popularity of the harbor, space is very tight inside the marina, but somehow Karen managed to swing Sea Rose around in her own footprint in order to back down to the open spot assigned to us. Boats were everywhere – leaving, arriving, going to the fuel dock. It was all one could do to just avoid a collision. With Steve and I on fender patrol, Karen slowly backed us down in between two powerboats. This can be a dicey affair, as the typical powerboat has a much higher deck, and the sides of the hull flair out more than a sailboat. Where to place the fenders so they actual fend off fiberglass becomes a guessing game until your hulls are lined up close. Karen put us on the dock gently and we settled against our neighbors without incident. Usually when you approach a dock, one or two people from neighboring boats will come over to help you with docklines and fend you off as needed. Several of the people next to us seemed to not even notice our arrival, nor care if our hulls came in contact. I asked them later if them would mind me untying one of their stern lines so we could get ours on the same cleat, and still, they seemed to care not a wink, returning promptly to their afternoon snooze in the sun. To be fair, the weekend finale of the Queen’s Jubilee was well underway and it seemed quite a few boaters were using the Queen’s good fortune for being in power an incredible 70 years as an enabler for late nights and leaky liquor bottles.

Yarmouth is a medieval-era town with just enough of an historical pedigree to attract mainland tourists but not enough to clog streets and stores. We took a stroll down the one main street to pause in front of St James Church, first built in the 1300’s, and destroyed and rebuilt several times. I silently wished the newlyweds, being showered with rose petals on their way out of the courtyard, a less turbulent path to old age.

The Queen’s Jubilee wreaked havoc on our dinner plans to celebrate Steve and Julie’s last night onboard, filling up the reservation books of the few restaurants in town. When the first question the hostess asks you when you step through the doorway is “Do you have a reservation?” you know it was the wrong night to play it loose and free. We finally found a sympathetic waiter who gave us a table in the bar area downstairs, an overflow from their main dining area that would have provided us with charming views but not the noise of the rowdy revelers down below on the street. Instead, we dined in the audio afterglow of quite possibly the loudest group of imbibing adults ever, nearly climbing over the tabletop at each other in wild exuberance or possible anger, it was not clear which. When their last round of drinks were drunk or spilled, and their bill paid, we could finally settle down to a pleasant evening reminiscing on the beautiful coastal sites we had seen together.

Our time of fun was not fully over yet though. Back on the boat, the wind had been steadily increasing out of the northeast, the only quadrant that exposed the marina fully to the rough seas of the Solent. With a logjam of boats shoved into a small harbor with the same fragility as a house of cards, wind was not a welcome late night guest. A four boat raft up directly to windward of us started to bend into more of an arc shape, causing the outermost boat to halt just off of our bow. One parting line or cleat would send boats into our bowsprit, spearing them like a lancer’s blow, but also crunching us into the dock astern. I really dislike marinas when the weather turns sour. There is just too many hard objects in close proximity. It was fun back at childhood sleepovers to pile on top of your friends on the living room floor, but now that we are adulting, it’s important to have some space. I would have happily paid a grand sum to slip Sea Rose out of the marina moshpit, and go anchor out. Oh well, another night of restless sleep.

Karen and I rubbed sleep out of eyes in the morning, as we bid adieu to Steve and Julie, who would take a few days ashore before flying back home. Our plan to divert to southern England waters to avoid the drab of the French coast had withstood its first week of trials, meeting all of the expectations for beauty, peace, friendship, and even a little drama. In short, it was a typical week onboard a sailboat!

Be sure to also checkout the video content on our LifeFourPointZero YouTube channel. We regularly post updates on our sailing adventures, as well as how to videos on boat repair, sailing techniques, and more!

That was a great read. Can’t wait to hear more details like this when you get back

It’s a date!