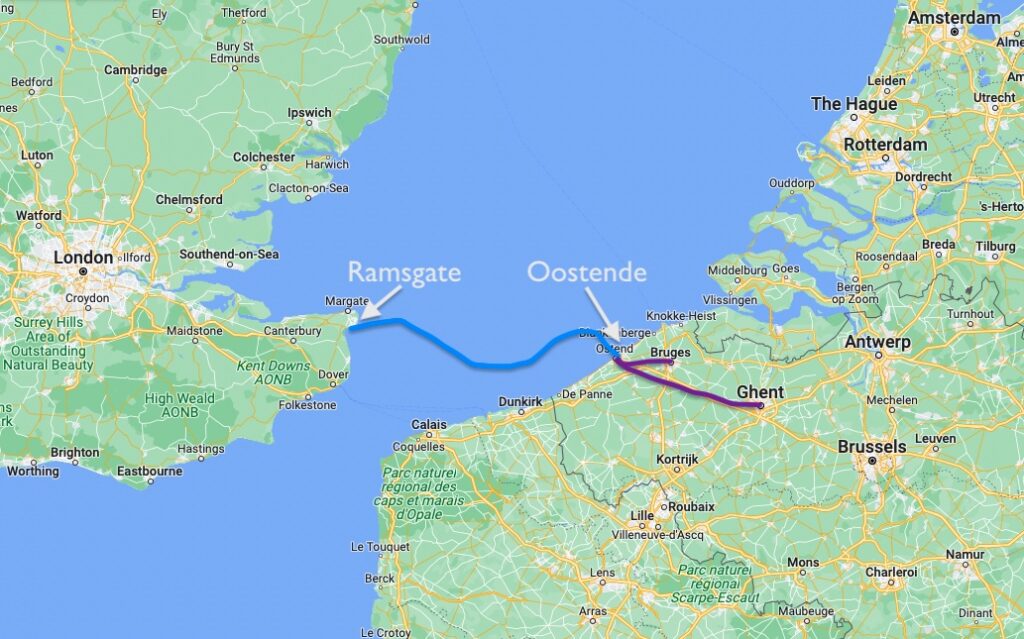

We had been in England for just two weeks, enjoying fine beer, authentic fish and chips, stunning cliffs and, oh yes, a ton of wind by which to sail. But Karen and I had our hearts set on the Baltic Sea this summer, and if we dawdled too long, our goals might just slip away. At 6:30am, we were off and away from the dock at Ramsgate, needing a full day to make the 65 miles back across the English Channel to Belgium. As the busiest shipping corridor in the world, our wits would once again have to be with us. In many ways, this would be more difficult than our earlier channel crossing from Guernsey to Weymouth. Here, the channel was not only more compressed, but the waters were pockmarked throughout with shoals, particularly on the Belgium side. The chart didn’t help much either. It was criss-crossed with shipping lanes and odd shaped purple separation zones. The majority of ships were following the dominant northeast/southwest routes, but a handful of ships were transiting east/west from and to the busy Belgium ports of Zeebrugge and Antwerp. In the center of it all was a counterclockwise roundabout of sorts, just like traffic circles on land except each ‘car’ here was measuring in at 600-1200 feet long.

As a warmup for our day of playing with ships, we set sail with moderate winds of 10-12 knots and beautifully smooth water. Workboats for the many offshore wind farms were throttling up and setting a course for invisible wind turbines over the horizon. Karen and I each tucked into our seats at the port and starboard helm positions as the autopilot guided us east, allowing us to sip our coffee and tea like a civilized couple ashore. When Mother Nature gives you a moment to ease into a day that you know is going to be long and challenging, you take her up on the offer.

Soon enough the wind and waves built, and we found ourselves on a near collision course with a huge container ship from Mitsui OSK Lines (MOL). This beast rang in at 400m in length, and our AIS was flashing red alarms with just a 0.3nm gap between our two courses (aka ‘closest point of approach’ or CPA). We had noticed earlier this summer that most ships call each other if the CPA is 0.5nm or less, so I grabbed the VHF and hailed the behemoth. The captain was OK with us holding our course, and seemed to appreciate that I had called. I’m sure most pleasure boats just wing it and hope the big ships see them.

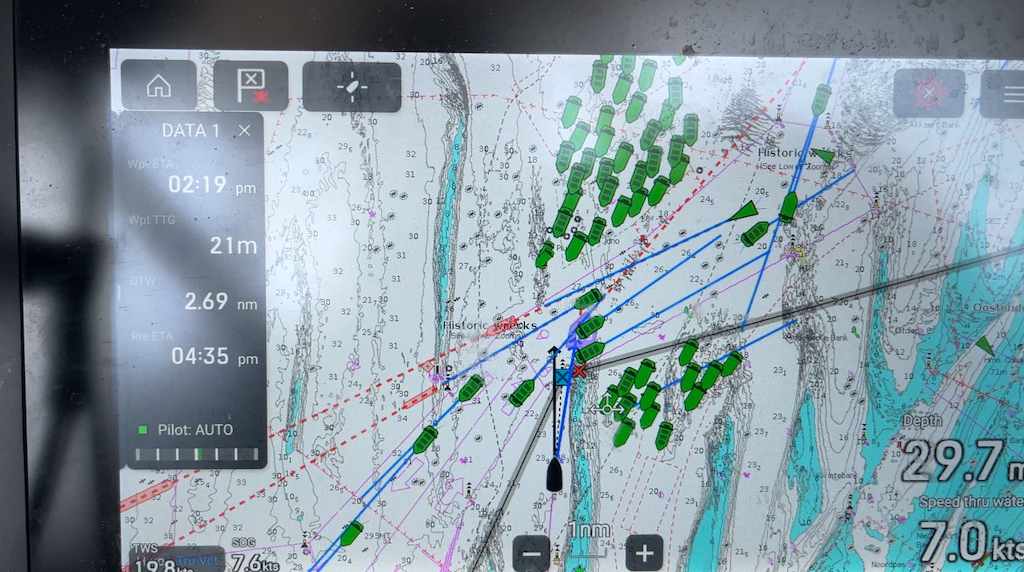

Ironically, we hadn’t even entered the official shipping channel (or ‘Traffic Separate Scheme’, TSS) yet. We altered course to avoid the five mile long South Falls ridge, a knife-edge of shallows where depths rapidly decreased from 40m to less than 8m. Although we would technically be able to cross over an 8m ridge with our 2m keel, good seamanship advised against such maneuvers. Safely on the other side, we took a course that would put us perpendicular to the first shipping lane. Trying to understand from the chart plotter which course was truly perpendicular was a mind-bender as ships entered and departed the roundabout just to the north of our position. We had good winds to keep us sailing, and all I wanted to do was get to the other side as soon as possible. As we entered the TSS, a slow moving tanker approached from our starboard side. Rules of the road dictate that a vessel approaching from your starboard has right of way. Our CPA was at exactly 0.5nm. We took the chance to hold our course and skip the radio call to the captain. All was good as we cleared their bow with enough of a safety margin. When crossing in front of these big ships, with their bow pushing out big waves of white water, it can seem like an eternity before that first glimpse of the far side of their bow, confirming that you are no longer directly in their path. Breathing a sigh of relief, we sailed onward into the purple safety zone between lanes, giving us time to assess the upcoming northbound traffic in our path. Since we were adjacent to the roundabout, some of these ships were turning from their northbound heading to take the roundabout path. Two ships coming up from the south were our immediate concern. I hailed the first somewhat slow moving cargo ship on the radio, telling them we were currently passing 1nm in front of them and asked if we should hold our course and speed. They confirmed with just ‘yes’, as if we lived in a world that charged for every word spoken. All was good until we noticed the second ship, a small and fast moving empty tanker, was starting to turn directly towards us. We had planned to safely pass behind their stern, but with their altered course, the CPA estimates were turning into frighteningly small numbers and getting smaller! I lunged for the radio and after a few more brief words, they turned even sharper to take our stern. Thank goodness it wasn’t a super tanker; this nimble offspring turned on a dime!

Next up on the northbound conveyor belt were two large containerships. We watched them closely but we safely passed several miles in front of them. At this point, we were on the far side of the TSS, a joyful position to be in. However, what we gained in safety from large ships, we lost to numerous shallow sand banks off of Belgium. This area is streaked with long skinny shoals running parallel to the coastline, making it a bit of a gauntlet to navigate around. As soon as we were clear of the TSS, we turned north and followed just on the outside, like riding your bike on the skinny shoulder of a busy highway. It was time to shift that derailleur to a higher gear. We rolled out the code 0 and rigged up the whisker pole for some downwind play time. But, as soon as we had everything rigged and trimmed, the winds began pushing 20 knots. That’s a no-no in our gradually evolving rule book of safe sail trim on Sea Rose. We immediately doused the code 0 and unfurled the jib, a much more comfortable setup without any loss in speed. So comfortable, in fact, that I lounged in the cockpit with a cold beer and bowl of peanuts as Karen went down for some much needed off watch rest.

Approaching on the hazy horizon ahead of us was a large number of ships anchored perfectly equidistant from each other, looking on the AIS screen like the formation of a well-rehearsed marching band. There had to be at least 40 of these jetliners of the sea, waiting to get into the cargo terminals of Antwerp and Rotterdam.

With limited choices away from the big commercial shipping ports, we selected the smaller Belgian port of Oostende as our welcome-back-to-the-EU destination. Still, commercial activity coming into Oostende was prominent enough that we were required to radio into Vessel Traffic Services (VTS) for clearance before passing inside the breakwaters, as more catamarans from the wind farms zipped by us and large support ships with odd shaped cranes maneuvered inside the docks. Just inside the entrance on the starboard side was the impressive if not intimidatingly named Royal North Sea Yacht Club. In my mind, the North Sea was a dark and fearsome body of water where even massive oil rig platforms cowered in the face of waves the size of skyscrapers. In not more than a tick of the clock hand, we had once been strolling amongst the virginal beauty of Southern England’s white cliffs. Now we had suddenly been thrown into the tempestuous North Sea. Fortunate for us, there was room at the inn. Karen guided us around a large dredging rig that looked like it had just completed its work in the yacht club, and settled us alongside a long empty dock. The only problem was the lack of water, at slightly more than 0.5m under the keel. Even though it was right at low tide, the stronger spring tides arriving over the next several days would drop the water another meter, so clearly we could not stay here for long. Instead of dropping lines and using the boat to probe for deeper water, I walked the dock with our portable depth sounder and found a perfectly deep spot just opposite the big dredge. As I double-checked depths, the crew on the dredge looked at me curiously. I know Karen and I do things differently than many boaters, and the fact that we are Americans draws the curious eye from locals regardless, so we get quite used to being stared at. Finally, the captain asked in broken English what I had in my hand. When I told him it measures water depth, they were amazed. They eagerly asked if they could look at it, take pictures and inquired where I had bought it. I had to chuckle. The irony of showing a dredger crew a device for measuring depth was not lost on me!

It had been a long day from our early morning start back in Ramsgate, so a walk around the shoreline felt fantastic. Soon, we found ourselves following the sound of music and the aroma of fresh cooked food. Belgium was apparently welcoming the crew of Sea Rose by launching a three day food truck festival. And where did all of these tall people come from, dismounting from their basket-clad bicycles and speaking perfectly good English? Despite many trips to Europe, we had never visited Belgium, and I was learning now what a mistake that had been. We’d have to make up for lost time.

Belgium is a tiny country in terms of physical land mass. It is about one-third the size of Portugal, and close in size to the U.S. state of Maryland. Yet, they pack a lot of people into this little gem, with a population of 12 million, translating into a density three times that of France. No wonder bikes are everywhere. If all Belgians had cars, you’d end up with one big grid-locked Los Angeles. The coastline of Belgium is even more minuscule, at just 43 miles, and largely made up of uninterrupted low-lying sandy bluffs. The shore seems to mimic the long rows of shallow sandy shoals just offshore. With many low-rise apartment buildings occupying these sandy bluffs, it doesn’t take long for a visitor to learn that the real attraction of Belgium is inland.

With that spirit, the next morning we found the ancient city of Brugge just a 15 minute train ride away, zipping us along at 100mph, leaving the car-bound tourists in the dust as they navigated the roadways that take at least 30 minutes to cover the same distance. The train dropped us off just outside the old city walls, providing us with a short refreshing morning walk to find the heartbeat of the city, Market Square. Here canals led away to the sea in the 13th and 14th century, boosting trade and making Brugge one of the most wealthy cities in Europe. If you spoke French back then you were even more well off, a language at the time associated with the elite.

This was our first experience of the summer as traditional land-based tourists. Compared to the last two Covid years, every sign pointed to a bustling recovery of summer travel. College students, the perennial moniker of European summers, were everywhere, and American-accented English could be heard front, back, left and right. While it was great to see travel returning to its historical heyday, selfishly I was a little disheartened to be shoulder to shoulder with so many other Americans. Covid restrictions had given our sailing exploits an extra air of adventure as we sailed for many weeks without seeing or hearing another native-English speaker. As the world becomes more populated, and planes, trains and automobiles carry everyone to distant corners of the earth with greater ease, it ends up being more difficult to discover the undiscovered.

We did discover that Brugge had a keen fascination with food and drink, and what better way to wallow in our self-pity than a Belgian brewery! The De Halve Maan has been brewing beer for 6 centuries, so taking care of two more hot, thirsty, wayward travelers at their door was well within their wheel house. This was a family business that didn’t rest on their laurels over the generational hand-offs. Today, the brewer (and brewess, as our guide was quick to point out) spend most of their time behind computer screens monitoring remote sensors and controlling flow with the tap of a key. This was not the typical micro brewery back home, with hoses draped willy-nilly over tanks and hand valves hinting at the heavily manual nature of the brewing process. For a software developer, I’m not sure there could be a better assignment.

Our tight, self-imposed schedule permitted just one additional day of exploring inland, with the city of Ghent the most logical choice just 30 minutes away by high-speed train. After one disembarks and safely navigates around the minefield of utilitarian bicycles parked on every available plot of land emanating from the train station, you find yourself enveloped in stunning medieval architecture. Towering cathedrals seem to pop into view around every corner, but most impressive were the many fine examples of stepped gable roofs, a feature thought to have originated here in Ghent from the 12th century before spreading throughout Northern Europe, particularly cities within the Hanseatic League. What started out as a cooperative between merchants and market towns eventually became a cartel of sorts, forming a near monopoly on maritime trade throughout the North and Baltic Seas. Clearly our species is challenged by the goal of free and fair trade, as the struggle to breakup monopolies continues today, but at least we got some cool architecture to gawk at from the water after choosing from a plethora of canal boat tour offerings.

If architecture isn’t your gig, how about famously reclaimed art? Ghent attracts visitors whose soul interest is The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, or simply The Altarpiece. This room-filling 12 panel masterpiece was first created in the 15th century and steadily restored and enhanced for several centuries after. So significant is the work that historians consider it to be the defining piece marking the artistic transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Apparently everyone wanted a piece of this master, leading to individual panels being separated and sold off to collectors and kings. But the real tragedy occurred during World War II when the Germans took possession, moving it around to various storage locations ostensibly to protect it from damage. Its final stop during the War was a salt mine, causing extensive damage to the paint and finish. If you happened to watch the 2014 movie ‘The Monuments Men’, the Altarpiece played a major role in the storyline. After many years of painstaking X-ray imaging and restoration by the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent, the entire piece finally returned to its home at St Bavo’s Cathedral for public viewing, behind a heavily secured and climate controlled glass enclosure. A thief, acting alone or with nationalist intent, will now have to get past the intimidating female guard behind the rope-slung boundary, whose stare was frightening enough to dissuade me from even pulling out my camera. So I’ll leave it up to your own imagination what it looks like!

Be sure to also checkout the video content on our LifeFourPointZero YouTube channel. We regularly post updates on our sailing adventures, as well as how to videos on boat repair, sailing techniques, and more!

All right – your AIS photo of the ship backups is far more impressive than what we have in the Bay!

Frankly I’d prefer the Bay…it was a whee bit too crowded with all of those ships moving to and fro!