As I have explained a few times to my older son, it is often best to assume the mind-set of expecting change as the inevitable. When we get too set in our comfortable day-to-day lives, even the smallest change like a new teacher assignment for a child can send us into a tail-spin. Something much larger, like the lose of a loved one, is much more disrupting emotionally and psychologically but we might be better able to deal with the big changes in life if we don’t head into that tail-spin for the smaller ones!

Of course, we recognized that this year would be one of constant changes for us — new “home” in ever changing ports, constantly changing means of provisioning, unexpected weather and boat maintenance and, potentially, a different language or currency to accommodate. So, sometimes we get a bit stuck to the things within our control, like our upcoming travel plans or the islands we want to keep on our “hope to visit” list. When something happens to alter this, we all need to remind ourselves that change is inevitable and then adjust to the new situation.

We have been in the US and British Virgin Islands since we arrived in the Caribbean on November 18th. A while back, we decided to stay there through at least January 10th as Tom had friends expected to visit. We were eager to move on, so after the guys from Bedford left us and we re-provisioned, did routine boat maintenance and received a shipment from the states, we headed away from the Virgin Islands in a southeast direction toward the island of Saba (SAY-bah). The seas were quite rough, which we expected based on the weather reports, but we decided to make the voyage since there were suppose to be favorable winds. We had a bumpy and tiresome 100 mile overnight sail as we beat into the wind on a close-hauled tack through heavy seas. This meant that getting any sleep down below was chancy at best, except for our youngest who slept like a baby! As the morning light showed off our destination, we seemed to be arriving unscathed.

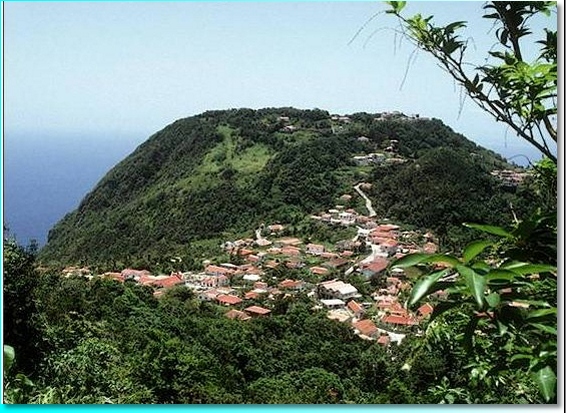

This is a great island that comes straight out of the ocean like the quintessential volcanic island that you might picture from a movie or book.

The island’s peak, Mt. Scenery, rises an impressive 3084 feet high and forms one of many popular hikes on the island. We moored at a spot called Ladder Bay. For much of the island’s history, this was the primary spot for getting ashore and up to the villages. Men would typically stand in waist deep water shuttling cargo off of ships to the rocky shore, and then up the steep winding 800 stone steps cut into the rock to the customs house above, which is still only half of the way up. Apparently, at one time they brought a piano up those steps!

With the way the cliffs rise so steeply from the shore, you might understand how the water depths drop rapidly not far off shore as well. There are no easy places to anchor and thankfully the island’s National Marine Park office has placed several moorings on the western shore. Still, without the protection of a harbor, cove, or inlet, the wind and swells rolled us constantly from side to side and we’d all quickly seek the comfort of a windy cockpit than the raucous scene down below in the cabin.

Though we were thoroughly exhausted from the overnight sail, we were anxious to venture ashore. A moderate dinghy ride through the waves takes you around the corner to Fort Bay, which, with a small pier, is the new location for unloading cargo. They have also built a concrete road up from Fort Bay to the first of two villages, deceptively called The Bottom. It is in fact a good 800-1000 ft up from the shore, via a road far too steep for US building standards, but they had to work with what they were given, which was a narrow ravine and a lot of manual labor. This road was all built by hand without the benefit of machinery. The pictures don’t do it justice, but just understand that you’d need the lowest gear possible to get your car up it, and plan on replacing your brakes every a couple of months for the steep trip down! Sometimes, our school work fits in real well with our travel plans, as the previous day’s science lesson for Zack was to find examples of simple machines, such as the inclined plane!

Saba is owned by the Netherlands, but while Dutch is sometimes heard, English is regularly spoken. Most products in the stores are priced in Guilders, which surprised us a first when we looked at half gallon of milk labeled 8.75 and which really was a moderate, isolated island price of US$ 4.85. If you are old enough, though, it is best to stick to the beer — single bottles commonly sell in the stores for about $1 and can be consumed as you walk out on the streets, or you can pick one up for about $2 at a bar (and still, remarkably, walk right out in the streets or into your car)!

After walking around the town, you quickly get the flavor of the European influences, with their narrow but spotlessly clean roads, tiny cars, and friendly people. Interestingly enough, a few years back they built an international medical school, which adds a couple hundred students to the existing island population of 1300.

Ok, remember the part of having arrived at Saba “seemingly unscathed”? In the morning after our rolly and bumpy night on the mooring, Tom was preparing the dinghy for going ashore as I was shutting up Thalia in hopes of a day of touring Saba. Tom abruptly came up off the dinghy and started putting his swim shorts on. “We have a problem”, he says while asking if I’ll get his snorkel and fins. “The rudder is freely moving back and forth with the movement of the seas.” I knew at once that this was a substantial problem, as we always tie down our wheel so we will point into the wind while on a mooring or at anchor. Our rudder should not be moving and is, therefore, broken to some extent. In this there was no doubt. The only question that remained was how severe the damage was. Tom dove under the boat and saw at once that the rudder had broken away from the rudder post. Meanwhile, the kids and I checked the main bilge and engine compartment bilge — no water entry, good. The post was intact and solid. What we now needed to determine was if the rudder was likely to fall completely off or just what was holding the rudder on. It took the entire day to determine our strategy for making our boat once again steerable!

We had a local mechanic named Daniel dive to look at it. After his inspection, it was decided that this rudder could not be repaired but must be replaced. He advised us to have it towed to the one and only pier to see if we could either remove the rudder from the post or secure it so that further damage would not occur. In the late afternoon, we were towed by a local fisherman to the small and very busy pier and were told that we needed to be off it by at least 7 am the following morning. We talked with a reputable boat yard in St. Martin who said we really needed to secure the current rudder for the pending 27 mile tow to his yard. Tom and I rigged up a cradle out of rope and, with successive dives to the bottom of the rudder, we had it holding the bottom of the rudder. We then secured lines to this cradle and pulled up evenly, tying off on various stern cleats, etc. We got the rudder as straight and stable as possible. All that was left was to secure a tow to St. Martin.

Throughout the day, local people recommended various fishermen who might be able to provide a tow for us. Seems this is not all that uncommon, as there is no haul-out facility in many of these smaller, remote islands. One gentleman named Leroy seemed an obvious choice. He travels to St. Martin each Friday to bring locally caught lobsters and red fish, and locally grown bananas. One problem, he had just developed a leak in his 265 gallon fuel tank and had diesel in his bilge and other undesirable places on his boat. He was also on the pier when we were, and he was pumping any diesel remaining in his tank out! He was filling 55 gallon drums on his boat’s deck. He and John (who runs a local dive shop) rigged up a system to pump diesel out of these drums and into his engine — bypassing his fuel tank. Once this problem was addressed he was confident that he would be able to tow us. He would also seek repairs at the boat yard to which we were headed! We reached an agreement with him at about 8 pm and and set our departure time for 5 am. We now had to rig up tow lines and bridles on both boats. We ended up with over 150 feet of tow line with multiple tie-off points on both boats.

Leroy had several local fishermen meet him at the dock at 4:30 in the morning to package up lobsters that Leroy would sell for them in St. Martin. It might have been mid-day given the number of cars, trucks, and fishermen that were working away. We got a bit of a late start, but the local fishermen cast off lines to us, pushed us off as best they could and we were under tow. What a helpless feeling! We pulled away from the pier at 6 am into a dark sea and sky. We each wanted to stand at the helm, though it was pointless. The one thing we had to keep our minds busy for our 3.5 hour tow was how to make the tow more efficient. It seems that our rudder just didn’t want to stay straight. It was determined to send us off to starboard. This was a strain on both boats so we put our heads together and came up with a few solutions that helped quite a bit. First, we dragged a heavily knotted 150-foot line off our port stern. This would provide drag to this side of the boat and hopefully straighten us out some. It did help, but was there something else we could do? We decided to raise a bit of our jib sail. The wind angle was off our starboard bow about 30-degrees and was holding at around 15-20 knots. This should push our bow to port. It did help! We didn’t know how much our modifications helped until we undid them as we approached Philipsburg, St. Martin. We pulled way off to starboard as we undid each aid. Here we are under tow by “Saba Girl” with St. Martin on the horizon.

The boatyard was ready for us to tie up at their haul-out docks and they had staff on hand to help us “land”! It worked quite well, given we had no steerage. We used our engine in reverse to slow us down once our tow boat sent us toward the dock. We were all very happy to have arrived without incident. An hour later, our boat was in the slings and headed for the “hard”! Not a sight I had expected to see for another seven months! Here’s our girl:

You will notice our youngest standing to the right. He is so enthralled with the process that he gets soaked from a passing rain shower!

Below you can see a close-up of where the rudder broke, and after that you can see the rudder from further back once a bracket has been removed.

We left Saba at 6 am on Friday, and by 5 pm that afternoon, we were officially living on the hard and would be here until probably the following Thursday. The mechanics removed the rudder and took it to their fabrication shop where they will make us a new one. We have decided to live aboard as it is high-season here now and hotel rooms are at a premium, if even available. Besides, the yard allows it, has shower facilities and we don’t have to move off then on again!

Meanwhile, Thalia was put on jack-stands and a ladder was set against her starboard boarding gate. She looks funny with no rudder and we all prefer her in the water, but we will make the best of it. We consider ourselves lucky to have been on a mooring when the rudder broke away. Sure, it was probably breaking away on our passage from St. John but she got us safely to Saba and are thankful for that. The first night on the hard, we had the captain/owner of Saba Girl (our tow boat) over for dinner and cooked some red snapper he gave us. Here is Leroy aboard Thalia:

We hope to make it back to Saba. We know we would be met kindly, just as we were helped by the great people of Saba during our short time on their island.