We awoke in the harbor of Inishmore on the Aran Islands to post-storm clear skies, a fresh breeze, and a full agenda. Our objective was the small fishing harbor of Fenit (fen-ISH), where, if our planning proved accurate, we could finally fill up with diesel and discontinue our miserly motoring tactics. The day looked promising for the 55 miles to go as we followed another sailboat out of the harbor and turned south between Inishmore and its close neighbor – geographically and phonetically – Irishmaan. Immediately, we were in the thick of it. Large swells, the detritus from yesterday’s storm, were being compressed in the narrow gap between the two islands. We have become quite aware of how angry compressed water can get. With still-limited diesel, we set sail and immediately took a close-hauled course through the gap, losing significant momentum each time Sea Rose’s bow came abruptly head to head with the next wave. White water and sea spray painted the cliffs to leeward on Inishmaan, ready to put us away should we lose our focus. I felt like a dental patient waiting with clinched fists, knowing that the pain will stop eventually yet wondering why it’s taking so long. Gradually the roar of the cliffs subsided and we found ourselves in open water with bigger waves but more elbow room to do our work. On flat water, we would have been able to easily make Fenit harbor on a single close-hauled tack but each wave introduced a little movement sideways instead of 100% forward. The technical wizard inside our chart plotter was following all of this activity closely and rather blithely painted a course-over-ground vector that incorporated the net effect of both movements. This vector, swinging in a 20-30 degree arc, had us not quite clearing the major points of land south of us. I tried hand steering to hold us on the razor’s edge of a heading that produced enough wind in our sails to keep us moving forward without luffing. At times we would be doing a respectable 6 knots through the water but then we’d slow to a painstaking 3-4 knots. With the big waves and choppy water, those 2-3 knots of extra speed make all the difference, with Sea Rose holding a steady course and driving through the chop instead of being at the mercy of the seas.

The concentration required to hand steer in these conditions is taxing and eventually we luffed up after slowing down in the waves. The genoa backwinded and we had no choice but to tack over. It was an inevitable consequence of pushing our luck to clear the first major point of land ahead, Loop Head. Tacking upwind is part of the reality of sailing. But if we could have made it in one tack it could have saved hours. On our new tack, we were headed nearly directly offshore instead of down the coast and it was painful to watch our distance to Fenit not change after an hour. However, for some reason, this tack was much smoother. Sea Rose sliced through the waves with equal measures of finesse and grace. Back on our original tack, we were barely making Loop Head but at least we had some windward miles in the bank. The winds steadily increased, forcing us to put reefs in both sails and making conditions in the cockpit uncomfortable as the boat came up the front side of waves and then slammed down the back side as it headed into the next trough. If we had been at sea for several days we would have been well adapted, but after two days of play on the Aran Islands, it was more than mildly unsettling. I really wanted to rest off watch down below, but, like looking over the vegetarian menu when all that is on your mind is a juicy cheeseburger, nothing looked appealing. I finally laid down on the lower side of the cockpit for a few moments of rest. The fickle wind soon lightened to 14-15 knots, necessitating us to shake out the reefs to keep the boat speed up in the waves. With these wind speed changes, it’s common for the wind direction to shift slightly too, and this time, it moved in a favorable direction for us to comfortably make Loop Head. Dark clouds started gathering upwind of us as we worked carefully to clear the next promontory, Kerry Head, without having to tack. Finally, we were in the last stretch with the large headland that formed the Dingle Peninsula giving us some protection from the ocean swells. Sea Rose was soon screaming along in flat water at over 8 knots, bringing us back in line with the original ETA I had given to the harbormaster of 5-6pm. Fenit Harbor was not a common stop for transient boats like us, and it was necessary to arrive when the harbormaster’s office was still open so we could get fuel and be assigned an open berth. As we rounded the breakwater, it was clear tourism was not the mainstay of the community.

A large ship, with sections of container cranes being loaded for export, occupied the entrance and further inside commercial fishing boats were double-rafted, with a search and rescue boat moored in the center. The fuel dock, if you could call it that, required us to back into a half-size slip with a bulky piling right where we needed to tie up the stern. The harbor master, standing on the breakwater above us, motioned to me to get ready for a small throw line. This was necessary because the fuel tank, a big industrial metal container looking more fit to refuel big commercial boats than meager little sailing boats, was on one side of a 10 foot gap with the fuel dock. The throwing line was then used to pass the nozzle, together with its oversized heavy rubber hose, across the gap of water to where we were berthed. We had to keep our thoughts of ‘Really, this is how it’s gonna go?” to ourselves lest we piss off the one man that has what we had been looking for since leaving Scotland. We finished the trapeze act without causing a hazmat disaster and soon we were settled on an amply sized face dock for the night, in the shadows of the hum of the big ship’s loading cranes. Looks can be deceiving and there ended up being a little tourism industry at work ashore. We walked past two hotels, the kind with a pub on the first floor and a few rooms on the second, tolerable if wee hours music was something you could sleep through. We found a wood-fired pizza business built entirely, including its open-air patio, of shipping containers. There was no time to negotiate a dinner plan. Two pizzas were ordered, delivered, and promptly consumed. It had been an exhausting day and satisfying the hunger was part of the pain management strategy. Body aches from working in the cockpit all day would take more time to subside. But fortunately we felt like the big hops would be over. It would just be a series of short legs to get around the Dingle Peninsula and on down to Kinsale.

Well, that was the hope. In the morning, after a glorious night of sleep, we awoke to a steady rain and for a brief moment considered staying put for the day. But after several checks of the forecast, it looked like we could be stuck here for 4 days before we could make it around the tip of Dingle. If we set out in the rain a short distance to Brandon Cove, that would shorten the distance for the next day and we could dodge the worst of the new storm system.

The wind was strong as soon as we left the protection of the breakwater and the big wind break of the ship in port. We were soon sailing nicely on a beam reach out the bay. The sky was even showing signs of opening up for the sun. But the wind kept coming. We put reefs in both sails. Our course to Brandon Cove required going out and around a narrow tongue of land in the bay and then making a 90 degree turn across the bay to the other side. As we approached the 90 degree turn waypoint, the seas, with a modest five mile fetch across the bay, were already starting to break, with white caps being strewn across the surface of the water. Our new heading took us past several small islands. With wind direction on our nose and close quarters, it would be risky to try to tack upwind, especially as the winds started gusting to 30 knots. How I longed to be back in Fenit, inside a snug berth with only the pitter-patter of rain drops on the deck.

We furled sails quickly and started the engine, but motoring upwind in 30 knots of wind is a real ordeal. Every few minutes, there would be a slight reduction in the size of the waves and we could make forward progress, albeit slow at 2-2.5 knots. But the rest of the time, we were painfully crawling along at 1-1.5 knots. Increasing the rpms only made matters worse, as the propellor can tend to cavitate as it spins in a little pocket of air. We tried ‘tacking’ upwind with the motor by heading 20-30 degrees to the side so were weren’t slamming directly into the waves with the bow. This seemed to help somewhat, but at 1-2 knots on an indirect heading meant that our ‘velocity made good’ was even less. Directly ahead of us was a beach with water churned up into a frenzy. The sand that gets mixed into the water in these areas can cause our depthsounder to show false readings, leaving us to guess distances off the land to determine, from the chart, how deep the water truly is. We tacked away to face a small but steep rock outcropping, until we were uncomfortably close to it before we tacked back to a point of land just barely to windward of the beach, confirming to us that while we were making ground to windward. It was at a speed no faster than a newlywed couple tiptoeing along the beach on their honeymoon, more focused on locking eyes with their lover than reaching any future destination. But this was no rom-com. We started to hear a new sound in addition to the cavitation – a bone-deep rumble and growl – as the engine strained under further pressure. I tried more throttle but the growling only got louder, which I took as a bad sign and dropped the throttle back down a couple hundred RPMs. The wind started hitting 35-38 knots and the bimini shook like the last leaf on the tree in autumn. When I peeked my head out to the side deck from the protected helm position in the lee of the dodger, I was shocked by how strong the wind pushed me backwards. Sea spray that struck the bow shot back past the stern in an instant like the speed of a bullet. Moments later, water would come rushing down the side deck into the cockpit and we’d have to lift our feet to avoid getting soaked. Once we cleared the beach, we started to see the boat speed climb to 3 knots, but then a wave, or a double wave, would slam into the hull and bring us to a near standstill. Inch by inch, the 16 tons of weight would slowly get moving again like a lumbering elephant slowly rising to its feet – unsteady, groggy, heaving. I couldn’t believe there would be so many large waves with only a few miles of fetch from the shore of Brandon Cove ahead of us. The tops of waves were being sliced off like a guillotine. But gradually we saw hope in the form of slightly larger digits on the knot-meter. The wind hit 40 knots but we were able to point at a slightly closer angle to the wind, improving our ETA. The wave heights decreased as the harbor came in and out view with the rain and clouds. Finally, we could make out a few fishing boats wallowing at anchor. It took a lot of coordination to not be blown over on the bow, but I started lowering the anchor as Karen positioned us far out of the way of the other boats. The anchor set immediately, I tied on the storm snubber and we both vanished to the cabin to strip off wet clothes and fire up the heater.

It was barely noon and it felt like we had gone the full 12 rounds in the boxing ring. We read and started planning our next navigation points, but it was hard to deny the stress level. Were we adrenaline junkies? Had we made poor judgement calls with the weather? Or were we making too many tight time commitments? There was no immediate answer but something would have to change.

In the morning, the cloud layer persisted but the air was devoid of horizontal rain. We set off to round the tip of the Dingle peninsula, at a point called Sybil Head. This was a renowned peninsula and few tourists to the west coast of Ireland would make the mistake to miss it. But the clouds shrouded the land from our view until we rounded the Head and turned back along the coast towards the town of Dingle, where the sun broke through and signaled the end, for now, of the nasties.

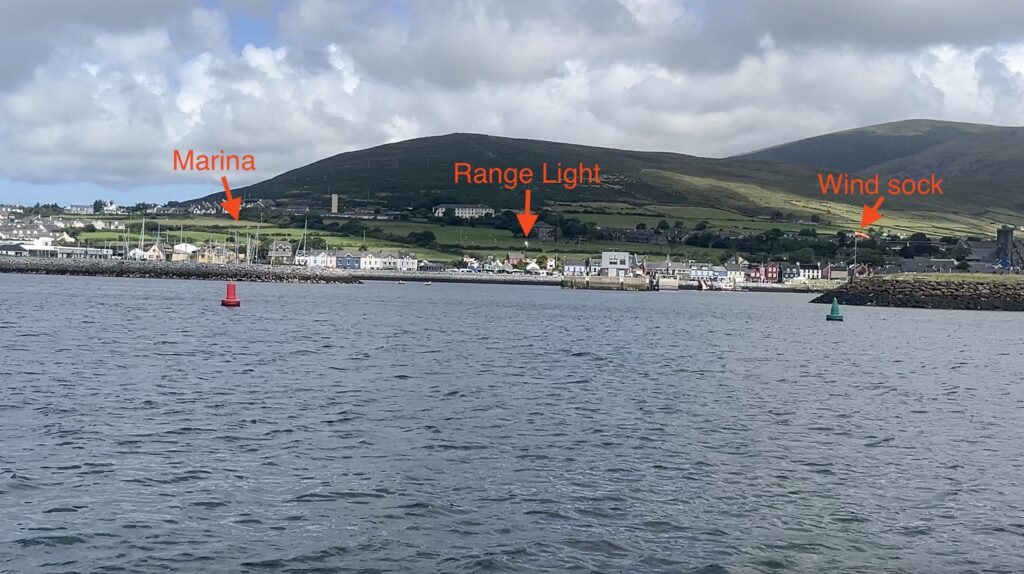

The channel into the Dingle harbour is long and narrow. Wisely, they installed a range light to keep mariner’s out of trouble. Normally these lights are paired, one lower in the foreground and another higher on a hill behind. If you can line them up, you are safely in the channel. This one was the 2.0 version. It was a single, laser-precise light. When you were in the channel, it showed white. If you were just 10-20 meters to the right it would show green; 10-20 meters to the left, it would show red. We were impressed!

If there is a town to spend an extra day at–needing recuperation or not–it is Dingle. The marina is modern, there is easy laundry, the grocery store is shockingly large compared to what we had seen in the last few weeks, and the town is densely packed with pubs. I had asked the marina manager where we might find some music (on a weeknight) and he responded with polite incredulity, “Pretty much every pub will have music…just walk around, listen, and stop in where it sounds interesting!” Indeed, I felt silly for asking the question after we passed pub after pub with a sandwich board outside stating some form of ‘Music Tonight 9PM’. The music scene here was the laid back informal kind that consistently turns up throughout Ireland and Scotland. A couple of musicians gather at a table reserved for them. Pints of beer are comp’ed by the bar tender. They will start playing a song or two, then pause to chat amongst themselves, maybe have a cigarette, definitely a few gulps of beer, and then they are back to playing. Likewise, the audience is quite casual. People mix and mingle, light conversation carries on, as if to not really notice the talented musicians just a few elbows away, but yet they acknowledge with a clap at the end of each song. The Irish have no idea how fortunate they are. We thought back to our many restaurant visits in Norway, a country I love dearly, but couldn’t recall even one of them having any form of live music.

Curiously, several of the pubs have an old-time general store layout to them, with long wooden counters with tall wooden shelfs behind, perhaps with a rolling ladder, as if they just finished selling their last sack of flour and clutch of nails, and now it was time to tap a keg or two. We then came across Foxy John’s Hardware. I was sucked in like a fly to a bright light with the window display of tools. Yet inside, a tiny counter of what I’m not sure – possibly a few door knobs and wood screws – was dwarfed by a large bar and many older men wedged into stools, all staring at me when I considered crossing the threshold for some shopping. I should have known. It was just like Brown’s Merchants in Tobermory, with their power tools and whiskey tastings.

Yes, the town parking lot is chock full of tour buses and the sidewalks are thronged with ice cream-toting toddlers and their bleary-eyed parents, but peel back a layer and you will find that Dingle has a remarkable culture and spirit.

Dingle is located on the northern side of the Dingle Bay. After two days of rest, we focussed on a piece-of-cake 15 nm crossing to Knightstown on the southern shore of the Bay. Immediately we were in 17-18 knots of wind and uncomfortable 2 meter waves. One of the challenges of the west coast of Ireland is the prevailing south to southwest winds, forcing you to be on a close-hauled course or to tack. To make the entrance to Knightstown, we trimmed the sails in close, barely making the heading. Despite the waves, Sea Rose was doing well until the skies filled with rain and the wind increased to the mid 20’s. We took reefs in both sails but the boat was still heeled over too far. A gust of wind came suddenly, leaving me without time to reach the jib sheet to slacken it, forcing us to heel over even further. Seawater came rushing down the leeward deck and into the cockpit while we were letting the sheets out. Before I knew it, my left leg was immersed in water up to my knee, letting water flow over the top of my sea boots like the spillway at Hoover Dam. Rain was so heavy, I couldn’t clear my glasses. In addition to my wet boots, water was finding its way into every little gap of clothing. All I could think was, “How did we get stuck in these conditions yet again?” The forecast had given no indication of this severity.

We tacked over to avoid what might be land ahead – it was too rainy to know for sure – and then tacked again, which put us on a straight course inside Valentia Island and soon enough, in the lee of the land. Knightstown has a particularly substantial set of pontoons that form a large square, inside of which would make for a very well protected marina. But somewhere along the way, funds dried up and the ‘marina’ is simply the outer box shape with a cavernous open interior. The upside is that dockage is free. Having been thrown back into the muck of a rough day’s sail, PTSD was rearing its ugly head. What we really needed, what is needed so often in times of angst, is a long walk in nature. We didn’t exactly find Yosemite, but the beauty and the fragrance of fresh, road-side wildflowers brought a sense of calm to the evening, and a mindset to endure another day of tough sailing, if that is what Nature had in mind for us.

Back out in the Dingle Bay at 7am the next morning, we motored into 15 knots of headwinds, a reality that once again was not what the forecast foretold. As we turned gradually south, the headwinds followed, moving to the east southeast when it was supposed to be out of the southwest. But at least we were entertained with the chosen names of the surrounding islands. There was the Bull, the Cow, and soon after, the Calf. Finally the wind clocked around enough so that we could set sail and start broad-reaching to the entrance of another name curiosity – Castletownbere.

In the same way that you back out of the way when the flight crew comes to board your plane, it was clear what the pecking order was here. The commercial fishing fleet was king. For the pawns like us, we were given a small dredged-out square area at the head of the harbor in which to anchor. We had seen only one other boat during the day, but we were pleased to be joined by three other sailboats, albeit a congeniality that was far more challenging than if we were all tied up to the same pontoon. Ashore, the grassroots fishing culture was hard to miss. Large spools of fishing nets and line were stacked at the landing and a smattering of pubs at the waterfront made me wonder how many fishermen stumble out of these venues at 2am after one too many and are looking for a reason to start a brawl.

We made it an early, Guinness-free evening with a few cheeseburgers grilled to soul-nourishing perfection on the boat grill.

The moment had finally come where the Irish coastline stopped heading south and started to turn east. With the prevailing south to southwest winds, this was an important coastal transition point as it allowed us to sail more and bash head-on into ocean swells less. Just out to sea was the famed Fastnet Rock with an iconic lighthouse on top and literally a boat-load of history that came with it. Back in 1979, the Fastnet Race, a 600 mile long challenge from the south coast of England, ended in disaster as 300 boats tried to round Fastnet and return to Plymouth. A severe storm struck the fleet causing boats to be abandoned, rescue crews to be stretched, and when it was all over, 19 fatalities could be counted. Back then, my mom thought the book written about the tragedy, Fastnet Force 10, would make the perfect gift, one that would discourage me from taking risks, maybe even get me into basket-weaving. But, alas, it didn’t fully work, although seeing the equally majestic and frightening rock out to sea from us did ring home the importance of keeping a good lookout.

For the evening, we chose the island of Cape Clear, just inshore from Fastnet Rock, with the caveat that if we couldn’t find space in the main harbour, we’d settle for one of the many anchorage options on the mainland. The pictures of the harbour revealed an extremely skinny concrete-walled opening into a tight triangular space that held just a handful of boats. The concrete entrance was built to hold back severe weather and storm surges, with a heavy steel gate designed to close the harbour in if necessary. On our arrival, it was a day full of blue skies and zero wind. Yet, it seemed impossible for us to round the tall concrete barrier without shaving off precious fiberglass on our hull. But why not, “Let’s try”, we told ourselves! Once past the barrier, the next challenge was trying to find a place to berth. Several sailboats had tied stern-to the one pontoon. The empty space they had left had subsequently been filled up with a cadre of RIBs, out for a day visit to the island. There was barely enough room for us to turn without striking a wall or another boat with our bow or stern. While we tried to assess how we might make this work, a small cabin cruiser overloaded with eager island visitors bolted in front of us and tied to a growing and unsteady raft-up of powerboats. So much for first come, first serve. We eventually maneuvered next to another sailboat and went safely stern to. Not a moment later, another mast could be seen moving past the barrier and soon another sailboat was side-tying to us. By the end of it, 15 boats had found a way, some more touch-and-go than others, to squeeze into this little haven of refuge.

The eagerness to visit was soon self-evident. By day, one could hike the steep rises and lush, flower-filled valleys. To cool off afterwards, people enjoyed the small beach and the picnic tables that rimmed the harbor. By evening, three pubs ran a vibrant business that satisfied young and old alike, whether for a beverage or a full dinner. The Paris Olympics were underway when we arrived at Cotters Bar and a large crowd made it hard to see what event was underway on the makeshift TV setup. But clearly it had to do with Irish athletes. Their women’s relay team were pulling out a surprise performance, vying for a medal. That is, until they were passed on the last lap. You never saw a shoulder-to-shoulder bar empty out so fast since the Guinness keg kicked! It was just Karen, I and the one man guitar playing band setting up for the evening. A crowded bar is annoying, but an empty one is even more so! We settled into an evening on Sea Rose, ensconced into the inner harbor as the lock-keeper had closed the gate at 9pm to reduce the tidal surge. In a lot of other places, this would be cause for claustrophobia, but with friendly Irish boaters tied up next to us, and a gaggle of kids running up and down the dock busy playing games during their last few weeks of summer, it was a reminder for us to savor these last few weeks as well. Soon enough, we would be leaving the Emerald Isle for points south, and with our pending departure came a deep appreciation for the kindness and light-hearted laughter of the Irish.

Challenging conditions but worth it to sail by Fastnet Rock. Many interesting races since the big event. Stay safe and enjoy.

Bob and Linda

Thanks Bob…yes it was fascinating being so close to Fastnet Rock. Take care!

Wow, that series of sails was decidedly NOT something I would ever want to experience! But those kinds of days always make for great stories & memories afterwards. “Remember when we thought we might die?” (Joy & I have a few of those.)

Life wouldn’t be complete without a few of those memories!